Museum Blog: Museum Decant – a conservator's perspective

Monday 18 September 2017

We have said goodbye to our old museum building and packed up all our musical instruments, paintings and other collections away to make way for the construction of a new building.

Decanting a museum is a big task. A lot of care and consideration goes into the packing and moving of precious objects and, as the museum conservator, it is my job to make sure they are properly looked after. Here's what really goes on when a museum puts its whole collection into storage.

Step 1: What have we got?

I began by getting to grips with the entire collection by doing a thorough overview of the types of items, materials, forms and weights we have and what condition they are in. As a new member of the museum team, this was an essential first step! The results were very interesting and I made some wonderful discoveries. It’s fascinating to look carefully at the earliest examples of keyboard and guitar instruments, for example, and to see how they were made. I also discovered some beautiful drawings on paper by John Singer Sargent.

| Drawing of Georgina Henschel by John Singer Sargent |

Step 2: What condition is it all in?

The old and precious instruments in our collections have been carefully preserved for us to look at. However, many of them are several centuries old and need a bit of tender loving care.

Many of our instruments were in excellent, safe and sound condition (despite a bit of wear and tear) but others were very fragile and required extremely careful handling. Most items still need loose parts to be re-glued and cleaned. For example, some of the decorative parts were falling off one of our harps, so it was important that I fixed the loose elements or packed them together with the instrument so they didn't get separated.

| This 1737 Viola d’Amore by Johann Ulrich Eberle definitely has a problem! |

To help me and my volunteers be consistent, I created a special 'condition survey' sheet, which we completed for each instrument. We have over 1,000 in our collection, which made this a very time consuming job. However, it was the best way of recording the most relevant details, as well as helping to identify any possible threats like moth or woodworm. We even took the large keyboard instruments apart to carefully inspect and clean them. Sadly (but perhaps luckily) I didn’t find anything as fun as a mouse nest or onion skin under a keyboard (believe me it happens!), nor did I find any hidden signatures or messages.

| This 19th century cornet by Antoine Courtois is unevenly tarnished |

One of the reasons for doing these types of surveys was to help me decide what to call back for conservation first. Over the next few years I will be doing conservation work on a number of our collection items in order to make them ready for the new display and to protect them from any further damage or decay.

| This Saung-gauk (Burmese harp) is a richly decorated instrument, but some of the elements have deteriorated over time and require urgent care |

Step 3: Where are we going to put everything?

Packing and storing a collection of precious objects is a difficult task and, in our case, had to be done with the help of hired professionals. It's important that the people packing sensitive and unique items have a good understanding of how to handle these objects appropriately and responsibly.

Companies tendering for the job were allowed to visit and see the instruments for themselves. The process began in January 2016 and included an estimate of the number and volume of items to be moved to storage, as well as contractual requirements. The visits to the museum happened in April and bids were received in June. We also performed suitability evaluation, which included site visits to the shortlisted storage facilities.

My role was to assist the process by providing information on basic requirements for packing, transportation, environmental conditions, and storage. It was very important to determine how the movements between storage and college would be handled during the years of renovation. Companies were evaluated according to the following criteria: Environmental Control, Security, Presentation of facilities, Retrieval of Materials.

Finally we appointed Harrow Green for the decant and Restore for off-site storage, and the countdown to an empty museum began.

| 'Recall 1' means this framed picture is in danger and needs to be prioritised |

Step 4: Time to get packing!

I put a lot of thought into the best way to pack, transport and store the objects. They have to be kept in a stable environment where temperature and relative humidity are set within safe range for each of the materials in our collection. These are very diverse and vary from wood, glass negatives, stone and textiles to metal, leather, painted and gilded materials. Each behaves very differently under different temperature and humidity conditions.

Quite a lot of packing materials contain chemicals that can cause damage to the objects inside over time. However, the science of conservation and museum supplies is really quite advanced. Wanting to avoid damage I chose acid free boxes, lined with Archival Polyethylene Foam and Ethafoam, or Plastazote LD45.

| Packing the portrait of violinist-composer Gaetano Pugnani |

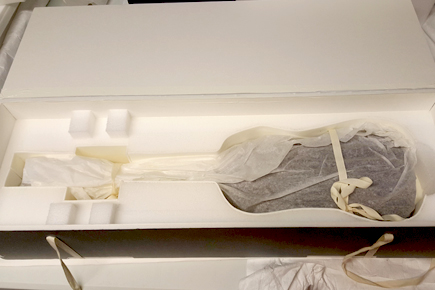

Wooden crates were lined with a vapour barrier and then foam. The vapour barrier was important as these crates are made of new wood and could give off gas. Some crates were also lined with a thicker layer of foam to reduce the impact of movement. These were used for extremely sensitive objects like the guitar by Belchior Dias (the oldest surviving in the world), which was placed inside a secondary box as well.

The most challenging item to pack was the clavicytherium: the earliest string keyboard instrument in the world. The wood is very fragile and it is an awkward, irregular shape.

| The Dias guitar being carefully boxed up |

Step 5: Getting everything out

With a state of 'organised chaos' it was crucial to keep track of everything that was coming and going. I had a master list of all the museum objects and our packing team was able to check out each instrument as it was packed and moved. Every box was barcoded and that number transferred to the museum database.

It is very important to understand how to handle each packed object as it is moved through corridors and hallways. Can we tilt it? Can we turn it on its side? Can it get through the door without putting pressure on it? How can it be loaded into and from a van and stored safely?

Our route out of the building involved a narrow corridor with a 90 degree turn, so moving large crates was really difficult. The uneven floor was lined with plywood planks and boxes and delicate instruments were rested on layer of foam specifically made to absorb vibration.

| Our clavicytherium is an awkward shape for packing |

Step 6: Sit back and assess

As with any project this size, there were a few trials and tribulations along the way, but by the end of the decant I was satisfied that the demanding job of collections management, logistics, organising moves, barcoding, photography and packing all went well. Considering the time constraints, it was a fantastic and rewarding achievement.

The proof of the pudding will be in the eating, so to speak, when all the items are retrieved in three years' time. As long as the instruments are physically well and no damage occurs I'll be happy.

This has been a great experience and I can't wait for phase two. Let the conservation begin!

Susana Caldeira

Conservator, Royal College of Music Museum